Volume 2

Volume 2 — College and Counterculture (1968–1972)

The Political Climate of 1968

The summer of 1968 was one of the most turbulent in modern American history. Just months before I began college, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles, shocking the nation. Only weeks earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated, triggering grief and unrest across the country. That August, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago descended into chaos, with police clashing violently with anti-war demonstrators in the streets. Television brought these images into American homes — tear gas clouds, chanting crowds, and the famous line: “The whole world is watching.” The Democratic Party ultimately nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey, despite many in the anti-war movement supporting Senator Eugene McCarthy. This left the party deeply divided and helped pave the way for Richard Nixon’s election as President in November.

Commuting to College

I started college at the age of 16 in the fall of 1968, living at home in Douglaston with my family. My car, shown at the end of Volume 1, was waiting in the driveway, but I couldn’t drive myself until my 17th birthday in November.

Mornings began with the Q27 bus rumbling down Marathon Parkway toward Queens College.

From day one, I made a deliberate choice to be more outgoing.

On those rides along the Long Island Expressway service road, I struck up conversations with fellow commuters,

turning the bus into a rolling introduction to campus life — friendships forming before the first lecture even began.

Orientation

Before classes began, I attended an off-campus orientation for new students. The event lasted overnight, with speeches from various campus leaders, casual hangouts, and the first chance to connect socially with other freshmen. We were also introduced to the process for registering for classes for the first time.

Registration Chaos

Registration that first semester was held in the college gymnasium, which was lined with long tables labeled for different departments. You had to figure out which courses to take with minimal guidance, then rush to sign up before the classes filled.

I ended up with a schedule that included liberal arts, math, physics, and an introductory computer science class.

By the time I arrived on campus, the atmosphere was already charged. A very vocal protest group — Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) — was constantly organizing rallies and trying to recruit new students like myself. They were relentless in their outreach, but I was completely non-political at the time and had no interest in joining. While the national headlines were dominated by Vietnam War protests and political unrest, my focus was on preparing for classes, meeting new friends, and adjusting to college life.

Joining Knight House

I didn’t join Knight House until after registration, when different house plans began soliciting new members. House plans at Queens College were like fraternities at other schools, but without any freshman hazing.

Knight House had its own space on Roosevelt Avenue in Flushing, and most of the members were older and more experienced, including two friends who would become influential in my college years — Michael Berkeley and Art Fishman. The group quickly became a hub of social activity and mentorship for me.

"The cafeteria was another central part of campus life — a lively social hub where students gathered at tables to talk, laugh, and share stories. It was the place to catch up with friends between classes, hear about upcoming events, or just relax over lunch. For me, it became part of the daily rhythm of college life, and often, the most memorable conversations happened there."

Social Life and Weekends

Those first months developed into a routine: weekends at Knight House with parties, card games, and camaraderie. It was also the first time I began dating — something I never did in high school. I went out with several girls during my first semester and enjoyed the new social freedom of college life.

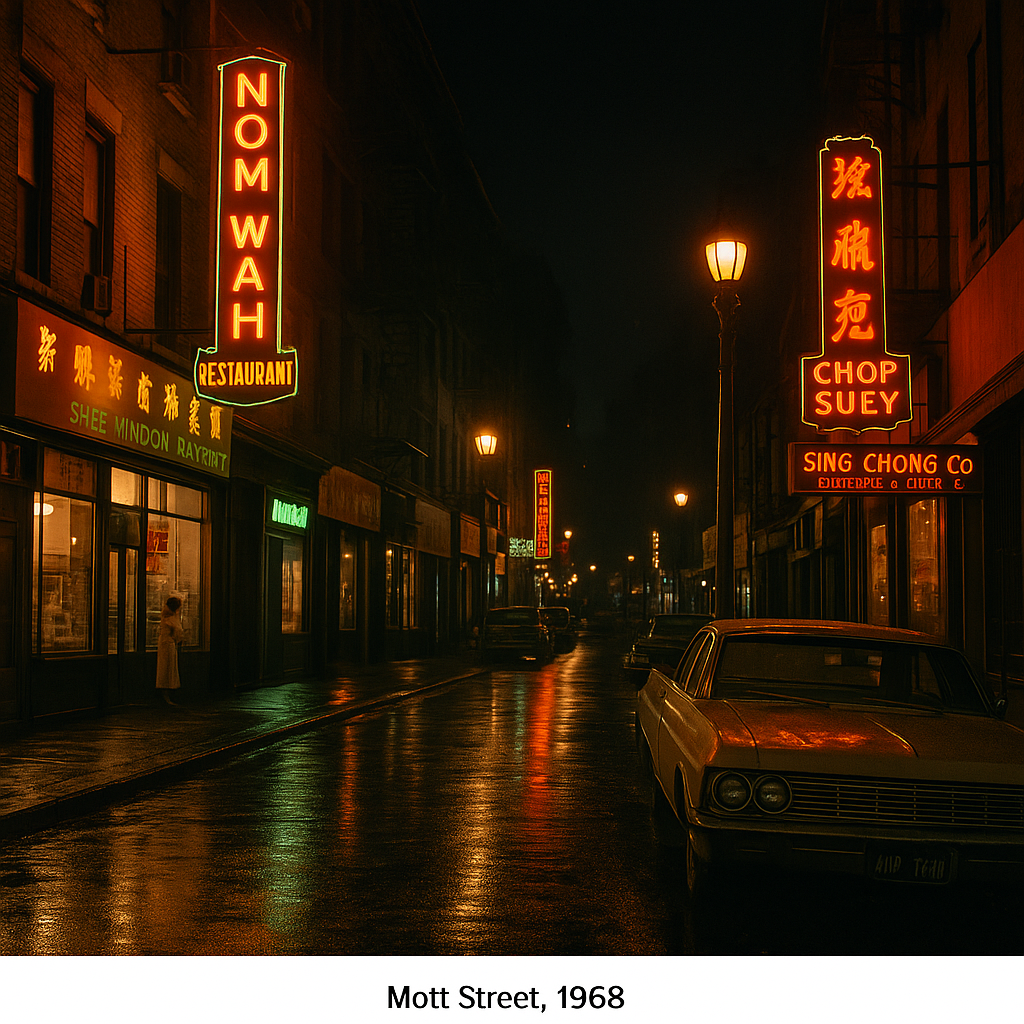

My 17th Birthday and Chinatown Adventures

On my 17th birthday — the first day I could legally drive solo in New York, having already passed Driver’s Ed and the road test — I drove to Queens College. It took me an hour to find parking, and I still had to walk three-quarters of a mile to class.

That night, I drove to the house plan to meet friends. Around 11:00pm and they convinced me to head all the way into Chinatown in Manhattan. I don’t recall whether we crossed the Manhattan or Williamsburg Bridge, but it became a weekly tradition: every Friday night at 11 PM, we piled into the car and drove to the same Chinese restaurant. Pork chow fun cost $0.80, shrimp chow fun $1.25 — cheap eats and great memories.

First Semester Classes

I was struck by the much higher quality of most of my college professors compared to my high school teachers, particularly in math and physics.

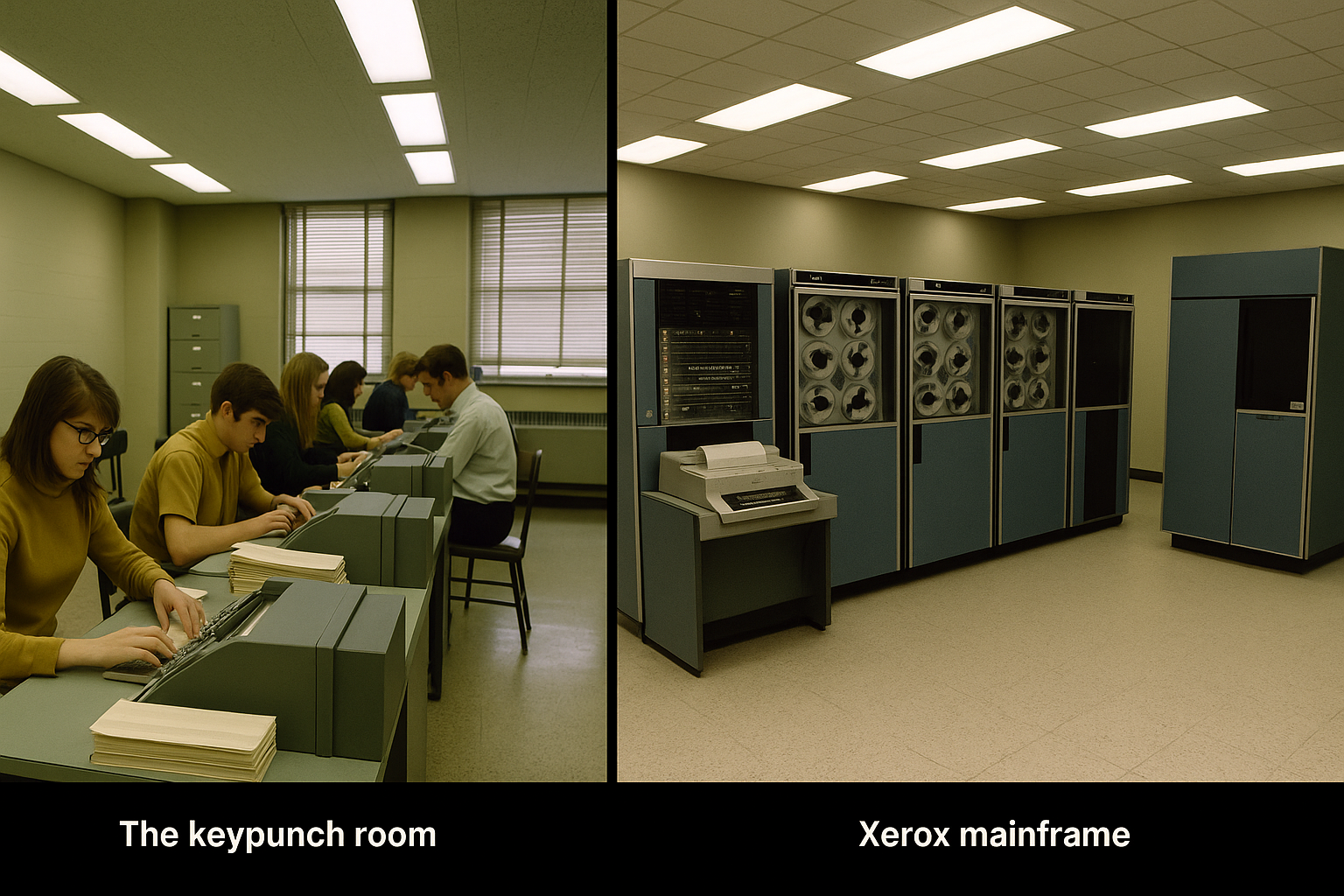

First Semester: Learning FORTRAN the Slow Way

Our intro computer science assignments meant writing FORTRAN on paper first, then heading to the keypunch room—a long row of machines where you waited your turn.

Each line of code became one punch card. When the stack was done, that was your “program.” We handed it in for batch processing on the college’s Xerox mainframe—one of only a few in the country—then waited a week (sometimes ten days) for results.

Most printouts came back like this:

SYNTAX ERROR LINE 3

Fix the line, resubmit, wait another week… and get:

SYNTAX ERROR LINE 15

That glacial feedback loop made it brutally hard to learn—especially compared to today’s instant compilers and to make things worse, I never actually saw the Xerox Mainframe.

Spring 1969 — First Romance

The spring term of 1969 brought a big change in my personal life. One Friday night at Knight House — where girls from outside Queens College often came on weekends to meet college guys, some of them still in high school — I met Debbie, who would become my first real girlfriend. I wasn’t interested in dating high school girls, but Debbie, who was out of high school and not attending Queens College, immediately caught my attention. We hit it off right away. Debbie was fun, smart, and loved music — especially The Doors. We spent a lot of time together that semester, going to movies, hanging out with friends, and sometimes just walking and talking for hours. For several months, life felt lighter and more exciting with her around.

Annual Queens College Canival

At the end of May, Queens College held its annual spring carnival, a tradition that brought together all the house plans and student groups. Each group set up booths, games, or displays to raise funds and show off their creativity. Since this was my first year, I wasn’t deeply involved in the building of Knight House’s exhibit, but I made sure to attend and help out. The campus was filled with music, food, and laughter, and I walked around visiting the exhibits, taking in the energy of an event that marked the unofficial close of the academic year.

By early June, as the school ended, our relationship had started to cool. We were seeing each other less, and I thought that might be the quiet end of it. But in late June, Debbie surprised me with a phone call. She wanted to know if I could drive her and two of her girlfriends to Woodstock that summer. We met at Knight House to talk about it, and that conversation would set the stage for one of the most unforgettable weeks of my life.

A Ride to Woodstock

In the summer of 1969, just days before the most legendary music festival in history, I found myself driving Debbie and two of her friends upstate. What began as a simple trip turned into an eight-hour crawl toward Bethel, a radiator rescue courtesy of passing Boy Scouts, and three days of music, mud, and a peaceful crowd unlike anything I’d ever seen.

Read the full story of the of Woodstock

Back from Woodstock, Into a New Academic World

We were home from Woodstock, the mud still barely washed out of our clothes, and the 1969–1970 school year was about to begin.

Queens College dropped a surprise on us right away: there were no longer any required courses. The old core curriculum was gone, replaced by complete academic freedom.

For me, this was liberating. It meant I could focus on the subjects I truly cared about — mathematics, science, and anything technical — without being forced through a maze of unwanted liberal arts requirements. But with that freedom also came the chance to explore areas I’d never considered before. I signed up for music appreciation, which deepened my understanding of the classical works I was already collecting on reel-to-reel and vinyl. I also enrolled in business law, which planted early seeds for the entrepreneurial ventures I would take on later in life.

Between classes, the student cafeteria became the center of my social life. This is where I began to form lasting friendships with people like Brian Fairweather, who would become my bowling and travel companion, and Celia, who seemed to be part of every trip and adventure I took during those years. We’d gather at the long cafeteria tables, sharing stories, debating everything from campus gossip to music, and mapping out our next great outing.

Queens College cafeteria, the social hub where friendships like mine with Brian and Celia were forged.

I turn 18 and have to Register for the Draft

On November 23, 1969, the day I turned 18, my father took me to the Selective Service office to register for the draft. At the time, all men were required to register within 30 days of their 18th birthday. I still had a student deferment because I was enrolled full-time at Queens College, which meant I was classified as 2-S and not immediately eligible for induction as long as I maintained my studies.

The Vietnam War was still escalating, and the draft was the main way the U.S. military filled its ranks. Until 1969, local draft boards decided the order in which men were called, often favoring those with connections or certain backgrounds. That changed with the introduction of the national draft lottery. The first modern lottery was held on December 1, 1969, but it only applied to men born between 1944 and 1950 — just before my birth year — so I wasn’t included. My turn in the lottery would come in 1970, and as it turned out, that year’s drawing would loom much larger in my mind.

The Band comes to Colden for New Years Day 1970

The idea for our first big event of the year came together almost casually over coffee in the cafeteria. Someone mentioned that The Band was playing on New Year’s Day at Colden Hall, right on our own Queens College campus. For music fans in 1970, this was a can’t-miss opportunity.

This concert was part of their tour supporting their acclaimed second album, "The Band" — often called the Brown Album — which had been released just a few months earlier, in September 1969. At that moment, The Band was at the height of their popularity and critical acclaim, already recognized as one of the most influential groups in rock music.

That night, in the intimate setting of Colden Hall, we got to hear songs like "The Weight," "Up on Cripple Creek," and "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" when they were still relatively new — the kind of fresh, electric performances that only happen when a band is still living inside the songs they’ve just created. The energy in the room was palpable, the crowd locked in, and we left knowing we’d just seen something timeless.

The Queens College Calendar, 1969–70

In those years, Queens College wrapped fall classes before Christmas. We returned on January 1 and took finals from Jan 1–15. After that came Intersession (Jan 16–Feb 1)—a perfect window for quick trips or one-off classes—before the spring term began in early February.

InterSession 1970 — Puerto Rico

After the excitement of the New Year’s Day concert, the campus eased into the quieter pace of InterSession — that short break between the fall and spring terms.

For me, it was anything but quiet.

Brian Fairweather — a good friend from Queens College with whom I bowled at Utopia Lanes — suggested we take a trip to Puerto Rico along with a few friends.

Among them were several girls from school, including Celia, who seemed to be a constant presence on these adventures, from ski trips to beach getaways.

We landed in San Juan with no real itinerary except to enjoy ourselves.

Our “routine” was simple: Brian and I would stay out late every night, wandering from clubs to beachside bars, soaking in the island’s rhythms.

We’d sleep in until nearly noon, then make our way down to the hotel pool around two in the afternoon — sunglasses on, moving at island speed.

The girls, meanwhile, were up early to claim prime spots by the pool, determined to return home with the deepest tans.

Puerto Rico was a perfect blend of warm breezes, new music drifting from open doorways, and the feeling of being far from the gray New York winter.

It was the kind of trip that tightened friendships and built stories to retell in the cafeteria once classes resumed.

Bowling Life at Queens College (1969–1970)

During this period, one of my favorite pastimes outside of academics and music was bowling—and not just casually. I bowled regularly with my good friend Brian Fairweather, even though he wasn’t in my house plan. We spent countless evenings at Utopia Lanes on Union Turnpike, competing in league play and in Kegler tournaments.

These tournaments were serious business—five-man teams, cash prizes, and a lineup of bowlers who could spin a ball like it was a ping-pong ball. One of our regular teammates was a friend named J. Power, an extraordinary bowler with an uncanny ability to control spin. Brian and I would recruit two other strong players, and more often than not, we’d finish near the top—sometimes second place—in these high-stakes matches.

Individually, I had my share of big moments. One day at Utopia Lanes, I rolled 11 straight strikes and finished with an eight for a 278, which earned me a trophy. My average hovered around 180–185, respectable even among competitive bowlers.

Through bowling, I also got to know Kenny Barber, the pro at Whitestone Lanes. Brian and I would sometimes head up to the Bronx to watch PBA pros in intense, cash-based head-to-head matches—a side of the sport most casual bowlers never see.

Bowling wasn’t just recreation; it was another way I built lasting friendships and embraced competition during my college years—blending skill, camaraderie, and a bit of a gambler’s edge.

New York Philharmonic Subscription (1969–1973)

My brother and I held Thursday-night subscriptions to the New York Philharmonic starting in 1969 and kept them for several seasons, through 1973. We sat in the orchestra, about three-quarters back on the aisle—close enough to watch the conductor’s face and the front desks, yet far enough to feel the hall bloom. We were usually the youngest people in our section.

Those first years bridged a historic shift: Leonard Bernstein’s charismatic, romantic programming giving way to Pierre Boulez’s more avant-garde, atonal/serial repertoire. Some of those Boulez evenings felt more like experiments than concerts—fascinating, sometimes baffling—but we stayed for all of it. Looking back, even the strangest nights became part of a shared adventure we still talk about.

Time for the Carnival

As April was ending, It was time for the Queens College Carnival and Knight House had something special in store for this year.

Carnival 1970: An Unexpected Sight from the Tower

In the May of 1970, Knight House decided to go all-out for the annual Queens College carnival. Our exhibit was ambitious: a large-scale replica of the campus administration building, complete with a tall tower. The plan was to have visitors climb the stairs to the top and then slide back down — a whimsical centerpiece for the event.

I was at the very top of the tower on a warm afternoon, hammering boards into place, when I paused for a moment to look out over the campus. From my elevated perch, I could see straight down the long central pathway that stretched toward the low administration building in the distance. The grass in the center was neatly framed by two parallel walkways, creating a natural stage.

What I saw next stopped me mid-swing. Far away, moving in perfect unison, were two long columns of figures dressed entirely in black. They were heavily armed and wore body armor that gleamed in the sunlight. From my vantage point, they were marching directly toward the carnival.

It was an unsettling sight — not something you expected during what was supposed to be a lighthearted campus tradition. They never actually reached us; at some point out of view, they turned off and went elsewhere. I climbed down and told everyone what I’d seen, and the carnival emptied fast. When things were declared safe, I packed the tools and drove home.

Only later did I learn the wider context: a riot had broken out in the cafeteria — chairs thrown through windows, police called in — and the whole moment was part of the national tension following the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970. Soon after, we were notified that the school year was effectively over, and the carnival was officially canceled.

Students were alerted that the school year was effectively over. Carnival was officially canceled. What I experienced on the tower that day was a strange collision between innocent Spring juxtapositions—and the unraveling of a very tense moment in history.

Summer of 1970 — Political Upheaval and Campus Unrest

The summer of 1970 was a period of intense social and political upheaval in the United States, with the Kent State shootings on May 4th serving as a major catalyst for nationwide unrest.

Immediate Aftermath of Kent State:

The killing of four students and wounding of nine others by Ohio National Guard troops sparked massive student protests across the country. Over 4 million students participated in strikes at approximately 1,350 colleges and universities — the largest student movement in U.S. history at that time. Many campuses, including Queens College, shut down entirely or ended their spring semesters early.

The Cambodia Invasion Context:

The Kent State protests were triggered by President Nixon's April 30th announcement that U.S. forces were invading Cambodia, expanding the Vietnam War despite earlier promises of withdrawal. This escalation fueled antiwar sentiment that had been building for years.

Continuing Tensions Through Summer:

- Student activism continued through the summer months, though at reduced levels as many returned home

- The Pentagon Papers controversy was brewing (though they wouldn’t be published until 1971)

- Antiwar demonstrations persisted, including the massive August 1970 march in Washington D.C.

- The trial of the Chicago Seven was ongoing, keeping radical politics in the headlines

Cultural and Social Climate:

The summer also saw the height of the counterculture movement, with music festivals, the rise of communes, and growing environmental awareness following the first Earth Day earlier that spring. There was a palpable generational divide between young Americans questioning authority and older Americans supporting traditional institutions.

The period marked a critical moment when many young people lost faith in their government’s honesty about the war and its willingness to listen to peaceful dissent.

When classes resumed in the fall, the political climate remained tense. In an unprecedented move, Queens College gave students the last two weeks of October off for political activity, underscoring the depth of the unrest.

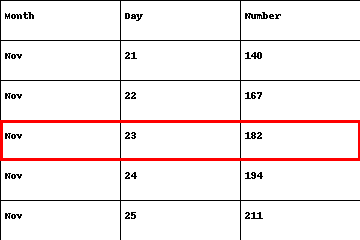

The 1970 Draft Lottery

On July 1, 1970, the United States held its second draft lottery to determine the order of call for men born in 1951. Since I was born on November 23, my birthdate was assigned lottery number 182. In the Selective Service system, the lower your number, the more likely you were to be drafted. While a number in the 180s meant I wasn’t in the most immediate danger, it still wasn’t far enough away from the cutoff to feel entirely secure.

In the context of the Vietnam War, this number carried real weight — the draft was not an abstract threat. Everyone my age knew their number, and those with low numbers often faced the difficult choice between military service, seeking deferments, or making life-changing decisions about their futures.

The New Semester Begins

The new semester began against a backdrop of political tension and uncertainty, still echoing from the spring shutdown after Kent State. In an unprecedented move, the administration gave students the last two weeks of October off specifically for political activity. This decision underscored just how deeply the events of the spring — from the Cambodia incursion to the Kent State shootings — had shaped the student body’s priorities and the institution’s willingness to accommodate activism.

But in the fall of 1970, one topic dominated the cafeteria conversations — the Vietnam draft lottery. My birthday came up at number 182, high enough to make me cautiously optimistic but still close enough to leave a trace of uncertainty. The cafeteria buzzed with the sound of people comparing numbers as if they were trading baseball stats. “What’s your number?” became a standard greeting. Those with low numbers often faced immediate and difficult choices. Several people I knew enlisted in the Army Reserves or the National Guard right away, hoping to serve under more controlled conditions rather than risk being drafted into active combat in Vietnam. For those of us with higher numbers, there was some relief — but no one knew exactly where the cutoff would be, so the topic stayed in the air all semester.

As it turned out, the draft boards eventually reached number 195 before the intersession in January 1971. That meant my own number, 182, had indeed been within range. When I heard that 195 had been called, it reinforced in my mind just how important my student deferment was — the narrow margin by which my life had taken one path instead of another.

The Washington Road Trip

Rather than using those two weeks for political purposes, I — along with my friends Brian Celia and others — decided to take a road trip to Washington, D.C. This wasn’t political in any way; it was simply a chance to see the capital and take in the sights.

We spent the two weeks exploring the city, visiting all the classic tourist attractions:

- The U.S. Capitol

- The Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial

- The Smithsonian museums

- Arlington National Cemetery

- And even a guided tour of the inside of the FBI building — something that would be unthinkable today.

We wandered the National Mall, toured the U.S. Capitol, admired the White House, and even got a guided peek inside the FBI Headquarters (then at the old Department of Justice building while the J. Edgar Hoover building was being completed). In between, we camped out at the Smithsonian museums, grabbed casual dinners, and talked late into the night back at the motel. Two weeks of history, architecture, and friendship.

National Mall on a crisp fall afternoon — our base camp for wandering.

FBI tour highlight: exhibits on forensics and law‑enforcement tools of the day

Inside the Capitol: rotunda, corridors, and a sense of the place at work.

White House walk‑by: quick photos, then on to the Smithsonian.

As the semester moved forward, I decided to take a chemistry course — not because it was required, since Queens College had no required courses at the time, but simply out of curiosity. The open curriculum meant I could take whatever interested me, and chemistry seemed like a change of pace. My history with chemistry, however, wasn’t exactly positive. Back in my first year living in Douglaston, my parents had given me a chemistry set. I did my experiments in the basement, and one of the early ones was to make a purple dye. It worked beautifully — but when I went to pour it down the basement sink, I didn’t realize my mother had been soaking her best linens there. Those linens came out permanently purple, and my chemistry set disappeared shortly afterward. That left me with a lingering dislike for the subject.

Still, I showed up to class, though I found it a bit dull. Around that time, I had also completed an Evelyn Wood speed-reading course and had become very fast at reading. Before our first test, I simply speed-read the textbook and sat for the exam. A few weeks later, some classmates confronted me, annoyed that I had “blown the curve” by scoring a 90. I hadn’t realized it at the time, but the class was graded on a curve, and my high score had raised the bar for everyone else.

During that period, I was dating a girl named Jody. She was determined to earn top marks so she could get into medical school, though competition was fierce and I’m not sure she managed to get the grades she needed. We dated for about a month, and one of the highlights was a trip we took together to the Caribbean — though I can’t remember whether it was Jamaica or another island. The days were warm, the breeze carried the scent of salt and flowers, and the pace of life couldn’t have been more different from the stress of campus life. But after the trip, our relationship began to fade, and we eventually drifted apart.

Intersession 1971 – A Ski Trip for the Non-Skiers

As the January break of 1971 approached, a group of us decided to do something different. We planned a ski trip—though, truth be told, many of us had never been near a ski slope before. Instead of booking a fancy resort, we rented a rustic cabin at an upstate New York campsite, the kind with wood walls, a fireplace, and just enough amenities to keep things cozy.

We did make it to a nearby ski area, but my own “skiing career” never really took off. I signed up for a beginner’s lesson, made a few awkward attempts to stay upright, and decided I preferred riding the ski lift up and then back down again. It was less exhausting and a lot warmer.

Snowmobiles were another story—I loved them. We’d take them out across the frozen fields and wooded trails, racing in pairs, sometimes competing to see who could throw the longest rooster tail of snow behind the sled.

At night, we’d head back to the cabin, dry out by the fire, and share drinks, stories, and plenty of laughs. Nobody cared whether you were an expert skier or a novice. It was about the camaraderie—a few days of fun, snow, and freedom before the semester picked up again.

Winter–Spring 1971: Fairways, Fillmore Nights, and a College in Crisis

As the winter of 1971 set in, my life found a rhythm that balanced discipline and pure freedom. By day, I was a member of the Queens College golf team, which played its home matches and held regular practices at the Black course in Bethpage. I spent many afternoons honing my game on Bethpage Black, a course already known for its difficulty — long carries, narrow fairways, and greens that punished even the faintest misread.

Competition wasn’t just limited to practice rounds. I remember matches at other venues — Briar Hall, a tight, tree-lined course that demanded precision, and Baltusrol in New Jersey, a storied championship layout whose prestige felt alive under my feet.

That season, two teammates stood out by more than their swings: Danny Rosenthal and Barry Kurland. Even though I was registered for my normal load of classes, once golf season started it was just as likely as not that I’d skip class for a match or practice, and I accumulated a decent number of incompletes.

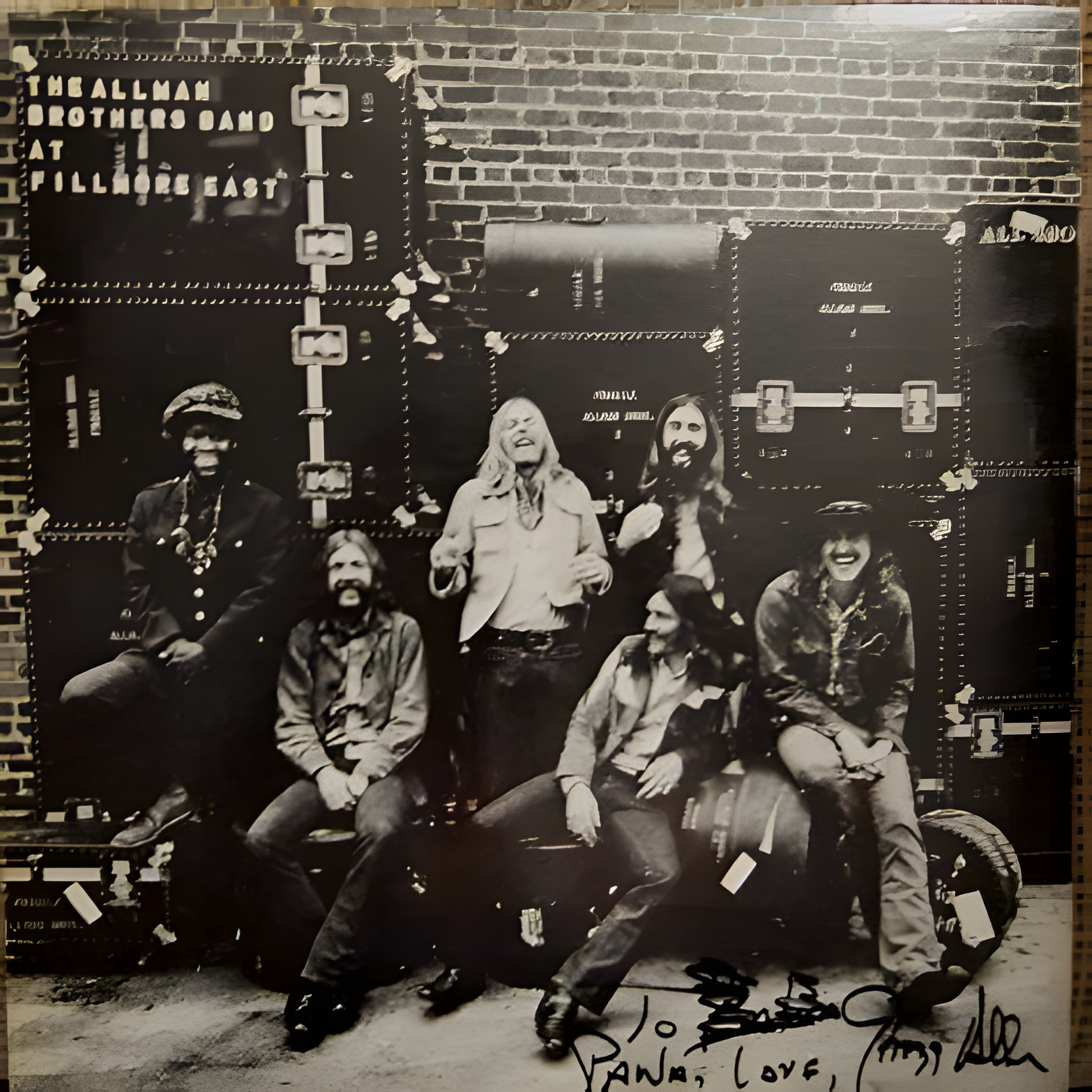

When dusk fell, I traded the quiet of fairways for the raw electricity of concert halls, becoming a regular at the legendary Fillmore East in Manhattan. The atmosphere — shadowed aisles, the murmur just before the first chord — was something you felt in your bones.

That spring’s concert lineup was one for the record books:

- March 13, 1971 — The Allman Brothers Band, part of their landmark At Fillmore East recording run — Duane Allman and Dickey Betts traded licks like a conversation of fire.

- April 20, 1971 — Ten Years After with The J. Geils Band. Alvin Lee’s guitar sang like lightning; Geils ripped through the night with raw power.

- May 4, 1971 — Jethro Tull with Cowboy, on the theatrical Aqualung tour — Ian Anderson’s flute notes hung in the air long after the set ended.

- June 26, 1971 — The Grateful Dead, headlining the Saturday night of the Fillmore East’s closing weekend. A charged farewell, as music and emotion collided in an unforgettable close to an era.

Meanwhile, the country was in turmoil — Vietnam, the Pentagon Papers, the 26th Amendment. And even on campus, unrest hit home. Queens College ended the school year early — before May — and canceled the spring carnival. I remember talking with friends about how strange it was that school never seemed to finish in the spring.

That gap — no lectures, no carnival, no closure — mirrored the larger uncertainty. My days on the course and nights at the Fillmore were a way to hold onto something steady when everything else felt in flux.

Fall 1971: Ice Cream Routes, Music, and the War on the Mind

Just after school started, a friend of mine at Knight House named Andy Moss asked if I would help him with his ice cream truck. I agreed — it sounded like fun.

The first thing he did was teach me how to drive it. It wasn’t a sports car-style manual; this was a three-on-the-tree column shift, clutch on the floor, lever on the steering column. It took an hour or two before I got the hang of it.

Once I could drive it, Andy showed me the route — cruising neighborhood streets, music playing, serving kids waiting at the window. Over the next few weeks, I ran the truck solo about six times. It wasn’t just popsicles — it was joy delivered, one cone at a time.

After that month on the route, I was left with more than memories — I had learned to drive a manual-clutch truck, and that’s a skill I carried long after the music faded.

Meanwhile, campus life was shifting too. In the cafeteria, conversations about Vietnam and the draft became daily fare. Debates at every table, protests growing louder outside — it was impossible to ignore. Nixon’s announcement of wage-and-price controls raised alarms about possible shortages, but in my own life — at home, with friends — nothing seemed to change immediately.

Semester routines continued: a walk to the bookstore became necessary at the beginning of each term. A detail I’ve never mentioned: I’d earned a Regents Scholarship before college, and since Queens College had no tuition, they sent me $125 per semester for books — a nice support for those bookstore trips.

I stayed active on campus — regularly attending New York Audio Society meetings, participating in Knight House life (though I skipped most parties), and diving deeper into advanced music courses. Classical music and theory began to hold even more fascination. I also kept going to New York Philharmonic concerts with my brother, a steady refuge.

Then as December neared, the draft news changed everything. The government announced that they had stopped calling numbers — they’d only gone as high as 125 from the July 1970 lottery (for 1951 births) .

I prepared myself: at year’s end, I declared myself 1-A, eligible for immediate induction. But on January 1, I was reclassified as 1-H, meaning I was no longer subject to processing. It was an enormous relief — I didn’t have to worry about being drafted myself, even while the war raged on around me, affecting friends and the nation.

1972: A Year in Motion

The year 1972 opened with the feeling that things were about to change — for the country, for Queens College, and for me. The war in Vietnam was still an ever-present backdrop, protests still flared on campus, and I had a full slate of classes, friends, and commitments. But as winter set in, one obsession began to dominate my thoughts: sports cars.

I had been poring over the car magazines for months, memorizing performance charts and technical write-ups. One statistic about the Porsche 911E stopped me cold — it could climb a 75-degree incline. That was the kind of figure that didn’t just suggest engineering excellence; it made the car sound almost superhuman. Every review I read seemed to describe it as something between a precision instrument and a living creature.

That fascination, coupled with the constant hassle of trying to park my big Pontiac Bonneville near campus, set the stage for the first big event of the year — the day my father and I walked into a Porsche showroom in Westchester and changed the way I thought about driving forever.

My First Porsche

Parking the Bonneville around Queens College was its own problem. More than once, I’d waste so much time circling for a spot that it interfered with getting to class. The idea of a smaller, more nimble car started to make more and more sense — and the fact that it happened to be a Porsche didn’t hurt.

One day, my father and I drove up to a Porsche dealer in Westchester. The showroom gleamed — polished floors, bright lights bouncing off paintwork. A salesman asked if I’d like a demo ride. I climbed into the passenger seat while he took the wheel, and we set off down the iconic, twisty parkway nearby. The way the car carved through corners was unlike anything I’d felt before — direct, poised, and alive. By the time we rolled back into the dealership, I was already sold.

My father asked me what I thought.

“I’d definitely like it,” I told him.

He negotiated quickly, and the dealer agreed to drop the price from the $11,500 list to $7,500 — a steep and immediate discount for the Irish Green 1971 Porsche 911E, a demo model with only a few hundred miles.

I drove it home from Westchester myself, being very careful at first. My only stick-shift experience had been helping a Knight House friend with his ice cream truck’s column-shift manual, so the Porsche’s short-throw floor shifter was new territory. I had a couple of rough clutch starts in the first twenty feet, but after that I settled in. By the time I reached Queens, it felt natural.

One quiet night on the Clearview Expressway, I let the speedometer sweep up toward 180 in the left lane before backing off — whether the gauge was optimistic or not, it felt like flying. I never tried anything like that again.

I was still concerned about trying to park the Porsche on the crowded streets around Queens College. Even though the car was smaller than the Bonneville, parking was always tight. It turned out my sister had been going to the United Cerebral Palsy of Queens on 164th Street, as she had been born with cerebral palsy. Up to that point, my father had been driving her there each morning on his way to work. He suggested that if I took over that responsibility, he would try to arrange for the college to grant me an on-campus parking pass so I could get to class without being late. The college agreed. From then on, and for the rest of my time at Queens College, I had the rare privilege of an on-campus parking space — a small but meaningful benefit that made both commuting and classes far easier.

Owning the 911E came with a few lessons. New York’s rough roads meant frequent alignments, and Porsche charged about $150 for the service — real money in the early ’70s. But every time I slid into the low-slung seat, turned the key, and heard that flat-six come to life, it felt worth it.

Intersession 1972: The Flamingo, the Grand Canyon, and the Pepto-Bismol Blackjack Run

Las Vegas neon, a white-knuckle Grand Canyon flight, and an unlikely blackjack streak — all in a single January trip. From the Flamingo’s casino floor to burro riders on canyon trails, this intersession was unforgettable.

Read the Story about our TripThe Porsche on the Ice Incident

A Brush with Death on a Second Date

Spring semester had just begun when I met her in Knighthouse — pretty, smart, with a tumble of curly black hair. It was the third week of February, and a heavy snowstorm had swept through the week before.

It was only our second time out together. I was driving the Porsche; she sat in the passenger seat, her curls catching the glow of the dash lights, as I picked her up for dinner. Around 7:30 on a winter night, we headed down the Whitestone Expressway toward that unusual left-side entrance to the Grand Central Parkway, right by LaGuardia Airport.

The main roads were mostly clear, but the storm had left its mark. The lanes were bare asphalt, yet here and there, meltwater and slush had pooled where they didn’t belong.

I eased into the left-side acceleration lane, building speed — not fast, just enough to merge. As I reached the curve onto the Parkway, the front tires sliced into what looked like harmless water. It wasn’t. Beneath the thin layer was ice. The steering wheel went light in my hands.

1. End of the acceleration lane, hitting ice

2. Middle lane, facing the wrong direction

The Porsche snapped into its first spin — headlights sweeping past the side window. Second spin — airport floodlights whipped through the windshield. If someone was coming at sixty in any lane, this could be it.

3. Stopped in the right lane, facing the correct direction, cars passing

Third spin — taillights and guardrails blurred together — and then, suddenly, stillness.

We were in the far right lane, perfectly facing forward, the engine stalled. I turned the key — the motor caught instantly — and we drove on as if nothing had happened.

Porsche Spinout Simulation

But I knew exactly what had almost happened. On the Grand Central Parkway, at that spot, at that hour, there was almost always traffic. Yet in those few spinning seconds, every lane was empty. It was as if the entire highway had paused for us.

I glanced at her — she met my eyes, a little wide but steady. “You okay?” I asked. She nodded. “We were lucky.”

It felt like more than luck. It felt like a miracle.

That was our last date.

The Girl with the Balance Problem

By March, I met someone new. She was beautiful, lively, and completely at ease in any room. To all appearances, she was perfectly normal — confident in her stride, steady on her feet.

That’s why I was stunned the first time it happened.

We were standing side-by-side at a football game. I looked away for a moment, and when I turned back, she was lying flat on the ground. No stumble, no warning — just down. It was almost as if she’d lost consciousness, but she hadn’t. Within seconds, she was getting back up, brushing it off as if nothing had happened.

Later, she explained it was something she’d lived with since birth — a strange balance problem that could strike without warning. Weeks might pass between episodes, or it could happen twice in the same evening. She never faltered in spirit, never seemed self-conscious about it.

Somewhere in those first weeks, she told me about her longtime childhood boyfriend — the man she always assumed she’d marry. But lately, she wasn’t so sure. Maybe that uncertainty was part of what brought her to me.

For two months — March, April, and into May — we were inseparable. Late-night dinners, spontaneous road trips, and plenty of private time together at the Knight house. It was a relationship that filled every corner of my schedule without me even realizing.

Then one night, she told me she had decided to go back to him. There was no fight, no drama — just quiet certainty. We didn’t really break up; she simply stepped back into the life she had always imagined for herself.

Enter Lori

That summer, the empty space she left was quickly filled. Lori arrived like a spark — and everything took a different turn.

During that period, I was in a steady relationship with Lori, and we spent much of our time together in Whitestone. Looking back, those two years were important for me — they gave me stability and companionship while I was wrestling with the pressures of school, work, and the larger world around me.

I grew a lot during that time, learning to face certain weaknesses head-on and to understand myself more clearly. In the end, I realized I wasn’t yet ready to settle down, but the experience left me with lessons about responsibility, balance, and what it really means to commit.

My Decision to Take a Leave of Absense from School

In the summer of 1973, my father suffered a heart attack at the age of 51. His own father — my Grandpa Harry — had died of a heart attack at the very same age, just before I was born. Fortunately, my father’s story turned out differently. He was visiting his osteopath for back pain when the doctor recognized the early signs of a heart attack and sent him straight to the hospital. That intervention saved his life.

With my father unable to work, I made the decision to take a leave of absence from college in order to help keep Ace Brass going. It wasn’t the path I had imagined for myself, but it was the step I felt I needed to take for my family.

The Summer of 1973: A Nation in Turmoil

As I stepped away from Queens College to help run Ace Brass, the country itself felt like it was spinning.

In June, former White House counsel John Dean gave explosive testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee, directly implicating President Nixon in the cover-up of the Watergate break-in. A month later, Alexander Butterfield revealed the existence of Nixon’s Oval Office taping system — a bombshell that would define the scandal. The fight over those tapes dominated headlines all summer, creating a constitutional crisis that eroded trust in the presidency and set the stage for Nixon’s resignation a year later.

Elsewhere, America was adjusting to the end of major U.S. combat operations in Vietnam following the Paris Peace Accords, even as the war continued for South Vietnam. The economy was faltering too, with inflation rising and the first signs of what would become the 1973–74 recession appearing on the horizon.

Despite the political tension, popular culture thrived: American Graffiti and The Exorcist hit theaters, Stevie Wonder and The Rolling Stones topped the charts, and the nation’s mood swung between cynicism and escapism.

That was the world I was stepping into — a time of upheaval and uncertainty — just as my own life was changing dramatically at home.

Sometime during the summer of 1974, I was paired in a golf round at Douglaston Golf Course with a woman named Barbara and her father. We hit it off, and although we dated briefly, we mostly became close friends. Through Barbara, I met Bryan Popko, who was a distributor for a company called SYBERVISION. That connection would become life-changing. SYBERVISION, founded on neuropsychological principles, offered programs like The Neuropsychology of Achievement and The Neuropsychology of Self-Determination. These taught you to reprogram your brain to overcome limiting beliefs, build confidence, and change behavior through mental rehearsal and visualization.

I took their personality self-assessment and scored 18 out of 21 on their “achievement traits” — meaning I already had a strong base. The training helped me fine-tune my habits. It was my first exposure to self-directed psychological transformation. Decades later, Scott Adams’ books, especially Win Bigly and Loser Think, further confirmed what I had learned — that memory is not fixed, it is rewritten, and understanding how our brains simulate confidence, identity, and belief is the key to unlocking success. Along the way, Gary Null’s work, like Who Am I Really, gave additional reinforcement. All of this helped shape the strategic way I’ve approached every opportunity in life — understanding how mindset is malleable and ultimately programmable.

In 1974, I returned to college after taking a year off to help run Ace Brass when my father had a heart attack in 1973. I was now serious about graduating and took three 18-credit terms, completing my degree by December 1975. I also took a course called Theoretical Mechanics taught by Dr. Banesh Hoffmann, Einstein’s former collaborator and biographer. The course covered advanced topics like Laplace's method for small oscillations, special and general relativity, and required you to write out your thinking — not just the answer. Even when I got answers wrong, he would give me A+ for my reasoning. After the class, he wrote a recommendation letter saying I was the best student he had taught in over 30 years and that he expected great things from me. I still have the letter to this day.

In January 1975, while still in college, I bought the MITS Altair 8800, a kit computer featured on the cover of Popular Electronics. Building it was painstaking — it had only 256 bytes of memory, and everything had to be hand-assembled. Eventually, I added static RAM and connected a Teletype ASR-33, which I used to input programs. It wasn’t until months later that I received a paper tape of Microsoft BASIC, which had been delayed due to legal issues with Pertec. With BASIC, I wrote an invoicing and accounts receivable system for Ace Brass that used cassette tapes for storage and printed documents on the Teletype.

By late 1975, I was using an IMSAI 8080 with an 8" floppy drive (160K capacity) and running CP/M. I was also attending computer festivals, helping small businesses using TRS-80s, and buying software from Lifeboat Associates — setting the stage for my next career move.

In May 1978, I married Joann. Later that year, we bought our first house in Douglaston.

Volume 2 ends there — a decade of exploration, technology, self-development, and personal transformation.